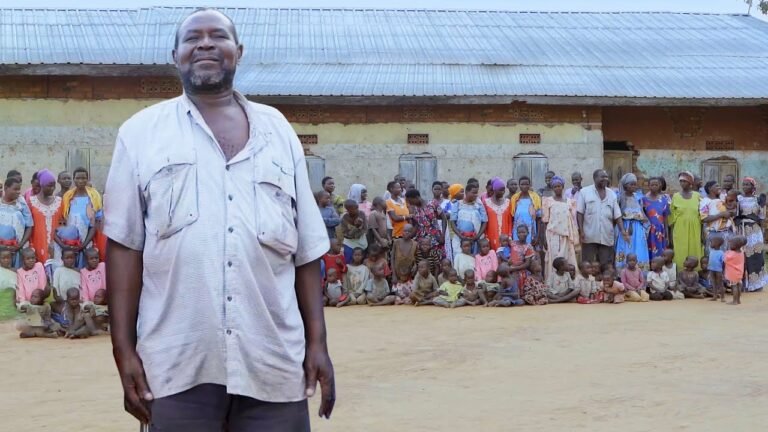

Alright, allow me to adjust my kikofiira and straighten my kanzu. My name is Mukiibi Hamza Katende, and I’m thrilled to delve into this fascinating aspect of our mother tongue, Luganda. Let’s get to it.

Uhhm, Have you ever been caught in a linguistic puzzle, when a seemingly simple word carries a weight of unspoken meaning? Language is more than just communication—it is a culture, an identity, and a history as Paul Kafeero states it in His song “Olulimi lwange“. Just the other night My younger brother jokingly told our little sister, “Oli gukazi gukulu, naye laba by’okola.” translating: “You’re a grown woman, but look at what you’re doing.”

This statement is usually made in Luganda to try and make some one see that they are doing things that are not of there age. It got me thinking – do we truly grasp the depth embedded in our Luganda words or we just say fwwaa. This sparked a deeper thought in me and if am to ask how many of us actually understand the stages of a female’s growth in Luganda, many dont know. As a proud Muganda and a Luganda enthusiast, I took this as a call to educate and document the beauty in our language and culture.

Luganda is not just a language—it’s a lens through which we see the world and understand our place in it.”

Mukiibi Hamza Katende

Our language, Luganda, isn’t just a collection of sounds; it’s a living archive of our history, our values, and our understanding of the world. Luganda is one of Uganda’s most widely spoken languages, primarily by the Baganda people of central Uganda. With roots deep in tradition, every word and term carries layers of meaning shaped by time, respect, and community values. In Buganda, women are highly regarded—not just as nurturers but as pillars of homes and culture. The terms “Omuwala,” “Omukyala,” and “Omukazi” aren’t just synonyms for “female”; they reflect life stages, responsibilities, and social roles.

These terms can be traced back to the woman’s embugo (yoni). This isn’t meant to be crude but rather a recognition of the biological journey that marks these different phases. Our elders understood this connection intimately, using it as a foundation upon which social roles and expectations were built. To truly understand omuwala, omukyala, and omukazi, we must first acknowledge this fundamental link, approaching it with the respect and sensitivity it deserves within our cultural context.

Consider this, language is the bedrock of our identity. When we lose the precise understanding of our words, we risk losing a part of ourselves. Just as the Nile defines our landscape, our words define our relationships and our understanding of each other.

Omuwala

Uhm, The term “Omuwala” is used to describe a girl between the ages of 11 and 18. It comes from the Luganda verbs okuwalawala or okusikasika, which suggest attraction or being drawn toward something. At this stage, girls start developing physically and emotionally, often beginning to notice boys (Abalenzi) and wanting to be noticed in return.

This is often the time when she begins to notice abalenzi (boys). Our elders, with their keen observation of life, captured this perfectly in the saying, “Embugo zomuwala ziba zimuwala wala zimuza mbalezi.” This translates to “A girl’s yoni draws her towards boys, making her seek their company.” It’s a poetic way of acknowledging the natural stirrings of attraction that mark this stage.

The omuwala might start paying more attention to her appearance, seeking ways to be seen and perhaps admired by abalenzi. Traditionally, this is also when girls begin learning responsibilities at home—helping with chores, being coached in etiquette, and gradually preparing for adulthood. In Luganda culture, this stage is guarded, protected, and respected because it defines a girl’s foundation.

A girl is not just growing physically; she is blossoming socially, emotionally, and culturally.

Mukiibi Hamza Katende

Omukyala

As the omuwala blossoms further, she enters the stage of obukyala. Now, omukyala literally translates to “a woman,” but within the traditional context, it carries a specific connotation tied to the act of “okukyaala” – to visit. This stage typically refers to women who are now exploring relationships, sometimes even cohabiting with partners, though not yet traditionally married.

Picture this: a young man, now likely omuvubuka (youth), might have started to establish himself, perhaps renting a room or an apartment. When his girlfriend wants to see him, she visits his abode and because they are visitors that is “Bajja ne Badaayo” meaning they come and they go back in English. They are visitors or bagenyi nti bakyaala ne badaayo. That’s why they are called abakyala. Hence, the term omukyala arose, signifying a woman in a dating relationship, one who “visits” her partner. They are, in essence, abagenyi (guests) in that context.

Importantly, its at this stage when a woman might start referring to her chosen partner from amongst the many as omwami – her man, her husband-to-be, or simply her significant other. Therefore it is traditionally considered less appropriate for omukyala to call a muvubuka “omusajja wange” (my man) in a possessive sense, as that term often implied a deeper, more established commitment, typically associated with marriage. omukyala stage is a period of courtship, of exploring deeper connections and potentially laying the groundwork for a more permanent union.

“To be Omukyala is to be seen, to explore, and to choose. It’s the bridge between youth and womanhood.”

Mukiibi Hamza Katende

Omukazi

Now comes the term “Omukazi.” Banange, If you’ve stayed with me this far, webale nnyo (thank you very much)! Omukazi isn’t just about age—it’s about responsibility. Derived from okukazza (to maintain, to settle, to keep ).

This stage is typically associated with marriage or widowhood, and often, the presence of children. The omukazi is the anchor of the home, the one who takes on the primary responsibility for the well-being of her family. She is the overseer, the manager of the household, ensuring its smooth running. Her role carries significant weight and respect within the community.

Being an omukazi is about nurturing, about providing stability, and about carrying the mantle of family responsibility. It’s a stage where a woman’s strength and resilience truly shine. While the modern world sees women in diverse roles beyond the traditional homemaker, the core essence of omukazi as a maintainer, a nurturer, and a pillar of the family unit remains a powerful and respected identity in Buganda.

Conclusion

Understanding these distinctions isn’t just about linguistic accuracy; it’s about cultural respect. Misusing these terms can lead to misunderstandings and even offense. It’s our duty, as custodians of this beautiful language, to pass on this knowledge to our children, ensuring they don’t fall into the trap of using these words carelessly.

As our society evolves, so too might the nuances of these terms. However, the underlying cultural understanding provides a valuable framework for appreciating the different stages of a woman’s life in Buganda.

Cultural teachings tie a woman’s development, attraction, and maturity to how she understands and manages her sexuality. This is neither vulgar nor disrespectful in traditional terms—it’s sacred knowledge passed down in ways that empower rather than shame.

Today, these terms may still be used, but their meanings sometimes get blurred or mocked, especially among younger generations. Some people now use “Omukazi” pejoratively, forgetting the dignity it once held. Others overlook the careful distinctions and use the terms interchangeably.

In many Western cultures, the female journey is defined by terms like girl, teenager, woman, and lady. These definitions are often chronological and don’t carry as much cultural symbolism as in Luganda. For example, “lady” might suggest elegance, while “woman” suggests adulthood. But in Buganda, each term implies duty, honor, or societal role.

Luganda is more than just a language—it’s a map of identity. The way we define a girl, a young woman, and a mature woman tells us everything about what we value as a people. Let’s continue to speak, teach, and respect these stages. Because every Omuwala has the potential to become an Omukazi of great honor.

Leave a Comment